By Howard Wang of Convoy Investments

The US debt ceiling crisis

Currently there is considerable political tension and bickering surrounding the US debt ceiling, resembling the dinner table dynamics of a financially troubled and debt laden family. Over the past few years, I have frequently discussed the escalating US sovereign debt level due to its growing significance in shaping politics, economics, and markets. Struggles like the ongoing debt ceiling issue are likely to become a regular part of our society.

In this letter, I provide context regarding the current debt ceiling impasse, which I believe will have limited short-term impact. More importantly, I delve into the long-term outlook on US debt, discuss some potential solutions to address this issue, and examine the implications for markets and the economy.

Near-term impact of the debt ceiling

While the current round of debt ceiling talks make for good political theatrics, it is unlikely to have substantial practical ramifications on the economy. In the short term, the market anticipates that the US government will likely resolve this crisis. Market indicators suggest a low 1% per year probability of default on US debt over the next five years, slightly higher than during the 2011 and 2013 debt ceiling crises

Markets expect the debt ceiling to be raised without significant practical consequences. The impasse has had minimal impact on US borrowing costs, which have continued to slowly trend down since the end of last year in line with inflation.

Additionally, the US stock market maintains its upward trajectory in 2023.

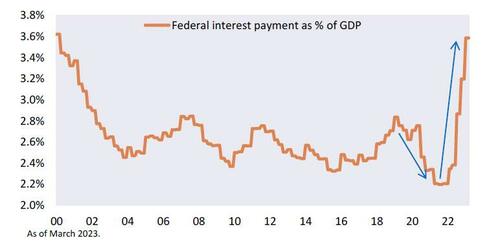

The relatively benign outlook is likely due to fact that the underlying economics of the US budget were greatly improved by the pandemic, which allowed the US to secure low financing rates while printing money to generate inflation, and boost GDP growth and federal tax income. However, as indicated by the following chart, this positive trajectory is rapidly deteriorating due to rising interest rates, a return to more normal levels of inflation, and a slowing economy.

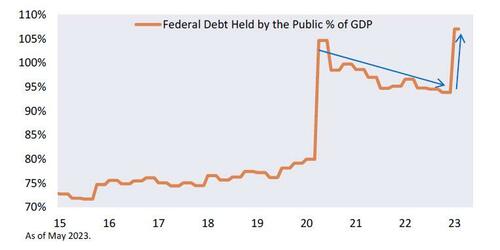

This pattern is also evident when considering the total debt level as a percentage of GDP. After the initial spike caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the ratio steadily declined but is now on the rise once again.

I largely agree with market sentiment that the current debt ceiling does not pose a significant immediate threat. However, I believe we are approaching a critical juncture where mounting debt levels, increasing financing costs, a slowing economy, and an expanding government footprint could compound and create an exponential problem.

What is the end game of continuously increasing the debt ceiling?

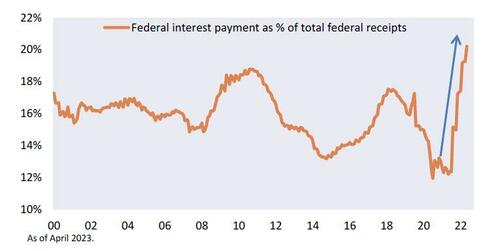

As the US has the ability to print its own money, the debt ceiling can be repeatedly raised for the time being. One key metric for assessing the sustainability is the cost of servicing debt as a percentage of the US federal government’s income (taxes). This is analogous to examining the monthly payments compared to income when determining whether one can afford a house. Let’s consider the rough math:

The current debt stands at approximately 125% of GDP. At the current 4% treasury rate, debt servicing costs would amount to 5% of GDP per year once the 4% cost extends to all maturities, which will take some time.

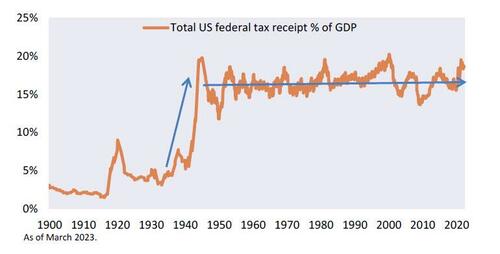

The federal government collects 15-20% of GDP as tax revenue, a consistent figure since World War II.

This means that 25-33% of federal income would go toward debt servicing, which is high but still manageable. For instance, at the personal level, the recommended threshold for housing mortgage payment is typically 30% of income.

Presently, this ratio is actually a bit lower, at around 20% of federal income. Much of the existing debt carries lower interest rates locked in from the last few decades. However, this ratio will rise rapidly as we retire older, cheaper debt and replace it with more expensive new debt. The following chart illustrates the portion of federal income allocated to debt servicing. We are already experiencing the rapid upward swing.

This ratio would deteriorate further if total debt levels increase or if market financing costs rise. For example, at 200% of GDP and a 4% financing cost, interest payments would consume nearly half of federal income. Alternatively, if interest rates were to suddenly rise faster than our GDP growth rate, the total cost of rolling and raising new debt would increase. Either scenario could initiate a downward spiral toward a debt crisis, where the federal government needs to do substantial borrowing to service existing debt, all the while facing higher cost of financing due to the deteriorating balance sheet.

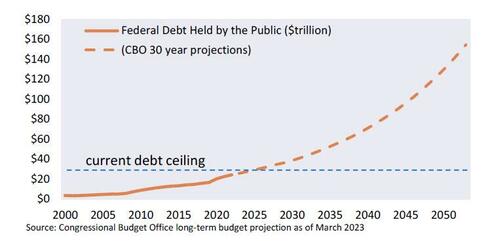

So, how significant is the debt problem we must address? The current debt ceiling stands at $31.4 trillion. According to projections from the US Congress, we will need to issue an additional $130 trillion over the next 30 years, projected to reach around 200% of GDP.

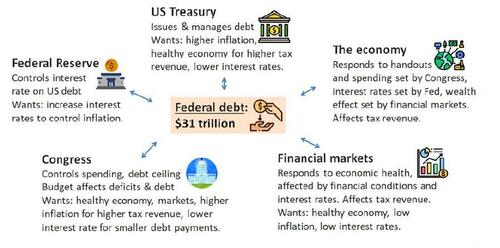

Issuing and managing $130 trillion in debt will pose the most substantial financial challenge for the next generation of Americans. Debt levels have now reached a point where they significantly impact politics, the economy, and financial markets. Gone are the days when Congress, the Treasury, and the Federal Reserve could operate relatively independently. We are already witnessing conflicts in managing objectives such as inflation, financial stability, recession, and the debt ceiling. These conflicts will only worsen. For instance, I believe the Federal Reserve will gradually shift its focus from managing inflation to assisting the Treasury department in managing national debt, albeit discreetly.

Debt has become pervasive, affecting nearly every aspect of our economy and government. The following chart provides a rough illustration of the interconnectedness that previously existed as more independent components.

So how do we deal with the debt?

The following are some of the levers that will determine whether we handle the debt issue in a healthy manner

or allow it to spiral out of control. With the exception of the last lever, all the proposed solutions have painful

side effects

1) Maintain higher inflation than interest rates

This approach would increase GDP income faster than interest rate costs, boosting income relative to debt. For example, post-Covid inflation has greatly benefited the US government’s budget as prices and income grew far faster than the cost of debt.

However, higher inflation often comes with higher borrowing costs and other economic challenges, as we have recently experienced. Therefore, we cannot rely solely on inflating away the debt. Instead, I expect the Federal Reserve to maintain steady moderate inflation slightly higher than their 2% target, likely around that of 10-year treasury rates (around 3-4%).

2) Decrease the value of the dollar

Lowering the value of the dollar is similar to generating domestic inflation in foreign exchange terms. This approach would enhance US competitiveness, reduce trade deficits, and increase GDP. Following a significant surge during Covid, the dollar has begun to depreciate, and I anticipate that the Federal Reserve will encourage a gradual decline in its value.

On the flip side, it is crucial to manage the dollar carefully since its stability has played a significant role in its status as the reserve currency, affording numerous benefits to the US. Additionally, as the dollar weakens, the US will experience imported inflation, which will gradually erode the average American’s standard of living. This cure will not come without painful side effects.

3) Use quantitative easing to keep borrowing costs artificially low

This has the obvious benefit of allowing the US to manage its own borrowing costs and to lock in longer term debt when long rates are appropriately low. Simultaneously, lower interest rates encourage shor-tterm growth, further boosting federal income. This strategy worked exceedingly well in the 2010s.

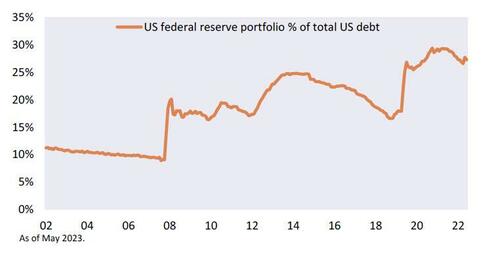

This strategy enables the US to manage its borrowing costs and secure long-term debt when long-term rates are suitably low. Simultaneously, lower interest rates stimulated short-term growth, further increasing federal income. This approach proved highly effective during the 2010s. However, it is worth noting that since the US government would essentially be purchasing its own bonds, there are limitations to this strategy. After all, the Federal Reserve cannot own the entire market. Since Covid, the Federal Reserve has held approximately 30% of all US debt.

I suspect this figure could be increased if necessary. Nevertheless, this strategy must be employed strategically as there are limitations. Carefully managing the financing costs is crucial because of its significant impact on the future of our federal balance sheet. A mere 1% change in financing rates can drastically alter the trajectory of our budget, as shown below in the projections from the congressional budget office.

4) Increase taxes

Raising taxes on a given size of GDP would augment federal tax income. Historically, the US government has collected roughly 15-20% of GDP as tax revenue since World War II.

Increasing taxes will create economic pain and face much political resistance, but may become necessary if the debt situation becomes dire enough. So we should anticipate potential increases in income taxes, wealth taxes, estate taxes, property taxes, and tariffs.

5) Reduce government spending

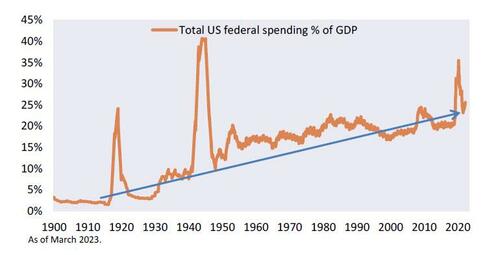

Reducing government spending is challenging since, aside from spikes and drops during wartime and times like the Covid pandemic, the size of our government has consistently expanded. As our country ages and programs like Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid become more expensive, we can expect government spending to continue growing.

Implementing any cuts will be painful and face considerable political resistance. However, we may find ourselves with no choice but to tighten our belts, so we should prepare for potential reductions in discretionary spending in the future, along with associated economic pains.

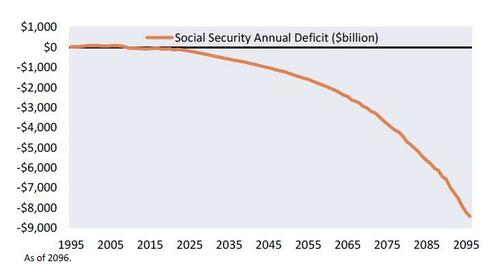

6) Related to above, semi-defaults on certain obligations like social security

I anticipate that we may witness soft defaults on mandatory spending, such as scaling back on Social Security. For instance, the Social Security Trust Fund is projected to deplete within the next ten years due to deficits.

Consequently, the program is anticipated to accumulate massive annual deficits, reaching up to $9 trillion per year by 2090, exacerbating the existing US debt issues.

It is highly likely that the next generation of US retirees will not receive the Social Security benefits promised to them.

7) Increase real GDP

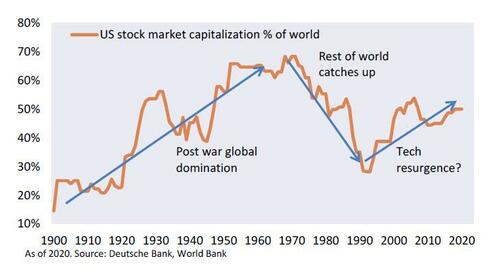

This is by far the most desirable solution, as it entails no downsides. It is also how the US managed to overcome its World War II debts. The success of this approach largely hinges on the US’s ability to maintain leadership in cutting-edge fields like AI. The provided chart showcases the long-term evolution of the US stock market as a proxy to the US economy. US stock market capitalization as % of the world experienced continuous growth from 1900 to 1970 as the US emerged as the world superpower after the two World Wars. Subsequently, the rest of the world rebuilt and advanced, with countries like Japan rising to prominence and taking away global share. Since 1990, the US has once again regained global market share, largely on the back of technological advancements.

I remain optimistic about the future of the US economy, primarily due to the massive leverage potential in technology, which tends to be a winner-takes-all industry. The head start and ecosystem that the US has cultivated in fields like AI provide our greatest hope for addressing our government’s precarious finances.

I believe that US debt will pose a significant problem requiring a combination of all seven levers to resolve. The more we can rely on the last lever of real economic growth, the less painful the process will be. I believe the US will grapple with substantial debt issues while simultaneously serving as a beacon of global growth and innovation.

From an investment standpoint, I expect high volatility, characterized by both extreme highs and lows. Diversification of currencies and assets will be crucial, especially as central banks are forced to become more prominent players in the market, resulting in more black swan events. However, I believe maintaining exposure to US equities, particularly in technology sectors at reasonable valuations, will be key to long-term success.

Because of my expectation of higher-than-anticipated inflation, I think it is important to hedge against inflation directly through commodities, TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities), and a small allocation to gold or cryptocurrencies if you believe in the long-term potential of that asset class. Specifically, switching to TIPS early on is recommended due to its relatively small market size compared to nominal bonds, which I hold a bearish view on in the long term. I believe gone are the days of the traditional 60/40 stock/bond portfolio. You’ll like need a 60/40 portfolio of stocks and inflation hedge assets.

Loading…

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/end-game-debt-ceiling