A study published Monday in Pediatrics reported a threefold rise in calls to poison centers for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, drug-related adverse events. A particularly sharp increase in calls beginning around 2009 coincides with the approval of guanfacine, marketed under the brand name Tenex.

Miss a day, miss a lot. Subscribe to The Defender’s Top News of the Day. It’s free.

A study published Monday in Pediatrics reported a 299% increase in calls to poison control centers related to therapeutic errors associated with treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents age 20 or younger.

In a press release, study co-author Natalie Rine, Pharm.D., said increases in medication errors are consistent with the rise in ADHD diagnoses during the past two decades, “which is likely associated with an increase in the use of ADHD medications.”

In other words more diagnoses mean more prescriptions, which lead to more errors.

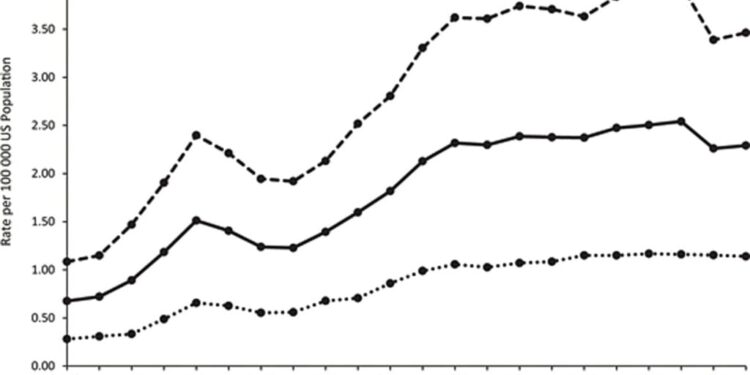

However, the authors of the study also said that while the increase in ADHD diagnoses from 2000 to 2009 may explain the rise in prescriptions and calls for those years, they believe the sharp uptick beginning in 2009 likely had another cause: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval of guanfacine, marketed under the brand name Tenex, to treat ADHD in kids.

The study’s authors wrote:

“The marked increase in guanfacine-related therapeutic errors observed in our study beginning in 2009 coincides with its FDA approval for ADHD treatment.

“In addition, the increases in serious medical outcomes and HCF [healthcare facility] admissions associated with ADHD medication-related therapeutic errors starting in 2009 were driven by guanfacine-related events.”

Figure 1 illustrates trends in poison center calls during the study period.

Although the FDA originally approved guanfacine for high blood pressure and not for ADHD, the drug received an endorsement from the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for use in children with ADHD in 2009, and full FDA approval to treat 6- to 17-year-old children with ADHD in 2010.

According to the study, therapeutic errors involving guanfacine were more likely to be clinically significant than for other ADHD medications, including stimulants.

Children who took guanfacine were more than five times as likely to be admitted to a hospital than those who took amphetamines or related drugs.

The authors attributed the higher admission rate in part to the drug’s extended-release formulation, which spreads the drug’s effect over a longer period of time than immediate-release medicines: An adverse event of moderate severity lasting 10 minutes may not trigger a call, but one continuing for an hour might.

ADHD is one of the most common pediatric neurodevelopmental disorders. A 2016 study reported that 6.1 million, or 9.4% of children ages 2-17 had received an ADHD diagnosis in their lifetimes, and 89% of those were still affected at the time of the report.

Approximately 3.3 million children — 5% of all U.S. kids — receive ADHD medication.

Children under 6 experienced twice as many serious outcomes

Researchers at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio — led by Gary A. Smith, M.D., Dr.PH. — examined both the characteristics of calls and their rising frequency.

They found the number of calls to poison centers for ADHD-related medications increased from 1,906 in 2000, to 5,235 in 2021, with an average of 3,985 calls per year and 87,691 total calls.

Only 17% of cases necessitated treatment but 2.3% required hospitalization (including 0.8% to a critical care unit).

Overall, 4.2% of cases resulted in a serious medical outcome that included agitation, tremors, seizures or changes in mental status.

Children under 6 experienced twice as many serious outcomes and were hospitalized at three times the rate of 6-19-year-olds.

Males and children ages 6-12 accounted for 76% and 67% of all calls, with 93% of adverse events occurring at home.

In 54% of cases requiring calls, the person took two doses instead of one, and 26% of the time they took the wrong medicine.

The National Poison Data System (NPDS), the source of data for the study, defines therapeutic error as “an unintentional deviation from a proper therapeutic regimen that results in the wrong dose, incorrect route of administration, administration to the wrong person, or administration of the wrong substance.”

A long list of drugs … and side effects

In addition to guanfacine, regulators have approved a wide variety of drugs to treat ADHD, most commonly the stimulants methylphenidate, amphetamine, lisdexamfetamine and modafinil, and the non-stimulants atomoxetine and clonidine.

Stimulants, which have an immediate and profound effect on ADHD symptoms, are considered first-line treatments. Side effects of these drugs include lack of appetite, weight loss, delayed growth, sleep disturbances, developmental delays and anxiety.

Doctors often prescribe non-stimulants when other conditions are present, for example tic disorders, or when stimulants might interfere with other medications a patient is taking.

However not all experts agree that children with tics should avoid stimulants.

Unlike many other ADHD drugs, atomoxetine was specifically approved for that condition but carries a long list of serious side effects, including psychosis.

Guanfacine and clonidine were originally approved for lowering blood pressure in adults. Both drugs carry warnings for circulatory, metabolic and/or emotional disturbances.

Clonidine’s original package insert does not inspire confidence in its use in children:

“The frequency of CNS depression may be higher in children than adults. Large overdoses may result in reversible cardiac conduction defects or dysrhythmias, apnea, coma and seizures.

“Signs and symptoms of overdose generally occur within 30 minutes to two hours after exposure. As little as 0.1 mg of clonidine has produced signs of toxicity in children.”

Under-reporting of mild cases may have affected study outcomes

The authors claimed their paper added to knowledge of ADHD treatment because earlier studies “broadly considered all pharmaceuticals” used by children, not specific ADHD drugs.

This point may be valid because most children with ADHD have at least one other health problem for which they may be taking drugs.

The study design acknowledged this by including only emergency calls for which an ADHD drug was deemed a “first-ranked substance.” That means the ADHD medicine was judged by a certified poison specialist to be responsible for the adverse event.

The authors cited only under-reporting as a study weakness. Cases may have been missed, for example, due to under-reporting of mild cases, or lack of rigor in determining first-ranked status in cases where children were taking more than one drug.

One weakness the authors mentioned only in passing was the possible role of prescribers. They listed 1714 cases of “iatrogenic” cases in a table, and referred to those cases once in the text. Iatrogenic means “caused by healthcare providers” — a medical mistake.

But the table also lists 1,789 cases in which the wrong formulation or strength was given, and 459 instances of “Confused unit of measure” — the confusion presumed to be on the part of the caregiver.

These are all caregiver mistakes. Added together, these 3,962 entries comprise 4.5% of all cases and would be the sixth-leading cause of drug reactions requiring an emergency call.

Also absent was discussion of the appropriateness of either drug type or dosage, diagnosis accuracy, length of treatment, adherence to prescribing instructions, whether doctors are prescribing either more ADHD drugs per patient or higher doses, or whether these drugs help in the long run.

ADHD symptoms persist into adulthood in about 80% of those diagnosed. An estimated 8.7 million adults in the U.S. are currently affected.

A market report by Credence Research estimates that worldwide sales of ADHD drugs will rise from $19.5 billion in 2020 to $34.8 billion in 2027. These medicines have been so successful financially, and unsuccessful therapeutically, that adults are now considered the “prime market” for what was once considered a childhood disease.

Emergency Calls for ADHD Medication Errors Up 299%, Researchers Say 1 Drug May Be Partly to Blame